Main Content

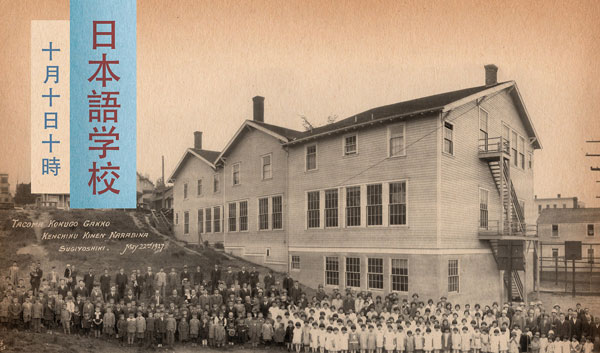

Between 1911 and 1942, a Japanese Language School known as Nihongo Gakko served a thriving Japanese community in Tacoma. The children from this community attended public schools, and after school was out each day came together at Nihongo Gakko. Here they learned the language, arts and cultural traditions of Japan, the homeland of their parents and grandparents.

After World War II, the Language School building stood mostly vacant for decades. By the time the university arrived and acquired the property in 1997, the building had deteriorated to a degree that it couldn't be restored with historic integrity.

The university promised to commemorate the history of Tacoma’s Japanese community with a permanent memorial. For generations to come, the memorial will tell the story of Nihongo Gakko through public outdoor sculpture and an interpretive plaque that will honor, celebrate and remember the school, the community that supported it and an important chapter in the history of our nation.

Unveiled in autumn 2014, the memorial sculpture called Maru is the work of sculptor Gerard Tsutakawa, a renowned Northwest artist best known for his "Mitt" at T-Mobile Field in Seattle. The work is part of the Prairie Line Trail where the former Northern Pacific rail line traverses the campus.

The rail line was converted into a public space that features a series of park-like gathering places joined by a landscaped bicycle-and-pedestrian pathway. This pathway is part of a larger trail system that travels down to Tacoma’s waterfront.

Accompanying the memorial sculpture is an interpretive plaque, recognizing the donors to this project and telling the story of the school and its honored principal, Sensei Masato Yamasaki. Greg Tanbara, son of JLS former student Kimi Fujimoto Tanbara, served as a lead volunteer on the project, along with Debbie Bingham, head of the City of Tacoma's Sister City program and a community leader.

University of Washington Tacoma has preserved the heritage of the Japanese Language School through academic research as well. Professors Lisa Hoffman and Mary Hanneman in 2003 received grants from the Founder's Endowment at UW Tacoma and the Ethnic Studies in the United States Fund at UW Seattle, to collect oral histories of the former students of the school, recording more than 40 interviews. The video below is a overview of that project. That research also formed the basis for a book, Becoming Nisei, released in 2020 by UW Press,

A history of the Japanese Language School

Between 1911 and 1942, a Japanese Language School known as Nihongo Gakko served a thriving Japanese community in Tacoma. Near the original Northwest terminus of the transcontinental railroad, the neighborhood above Commencement Bay included hotels, laundries, banks and other businesses. It also included the homes of hundreds of Japanese immigrant families. The children from this community attended public schools, and after school was out each day, came together at Nihongo Gakko. Here they learned the language, arts and cultural traditions of Japan, the homeland of their parents and grandparents.

When Japanese-Americans living on the West Coast were ordered to internment camps after Pearl Harbor, the U.S. government used Nihongo Gakko, the heart of the community, as the gathering spot for registration of Tacoma’s Japanese-Americans. Most of these people spent the duration of the war in camps — with the notable exception of those who served in the U.S. Army (including several recruited to military intelligence because of the language skill they had developed at Nihongo Gakko).

Building the School

From the 1890s into the 1940s, Tacoma's "Japan Town" was defined by a wide range of businesses, hotels and homes primarily located between S. 11th to S. 21st streets near Pacific Avenue. The district included the original locations of Uwajimaya and the Japanese Consulate.

The ethnic community raised funds to retain the prominent architect Frederick Heath of the firm Heath, Gove and Bell to design and build the school, which opened in 1922. In 1926, an expansion was completed to better serve the growing population and function as a gathering place for community meetings and events.

After the War

Tacoma's Japan Town did not revive after World War II and the internment of the city's Japanese citizens. For some 40 years the Japanese Language School building stood mostly vacant, eventually coming into the possession of the University of Washington, which found calligraphy charts still hanging on its walls. In 1997, the permanent UW Tacoma campus opened a few blocks down the hill from Nihongo Gakko — in readapted historic brick buildings. But the wooden Japanese Language School building had not weathered the passage of time well, and an architectural consultant determined the building had deteriorated too much to save. On the consultant’s recommendation, the University decided not to invest in expensive reconstruction of a building that would ultimately lack historic integrity, but, instead, to put its efforts into preserving the heritage of the school.

To that end, before the building was taken down in 2004, many former JLS students gathered for a special day at UW Tacoma — with tea ceremonies, flower arranging, calligraphy, Iaido, singing and reminiscence. Since then, UW Tacoma has maintained the conversation with Nihongo Gakko’s former students and some of their descendants. UW Tacoma faculty have recorded oral histories from former students. Historic photographs of the school and those it served — along with the rescued calligraphy charts — are displayed on campus.

Lasting Impact

In their oral histories, students of the school consistently recalled the tremendous influence of the principal, Masato Yamasaki, and his wife Kinu. In their teachings, the Yamasakis personified the community's pride in being American while working to help children embrace their cultural heritage. They encouraged children to live by a moral code that called for them to be highly ethical and respectful — to behave as model citizens representing their community during a time when discrimination against Japanese and other people of color was entrenched. Mr. Yamasaki, as a noted community leader, was among the first to be arrested as World War II began. He died in 1943 in the Lordsburg, N.M., isolation camp. Mrs. Yamasaki passed away in 1946 in Tacoma.

Alumni of the School

Many of the students who studied at the school went on to distinguished careers across the United States as physicians, dentists, nurses, engineers, attorneys, teachers, university professors and corporate managers. One became a federal judge. Alumni of the school served in the highly decorated 442nd Regimental Combat Team and in the Military Intelligence Service, where bilingual skills were often a prerequisite.